Xu (2019) distinguishes between three historic world food regimes: the period when the UK was the world’s major food importer (1850s-1917), when the US dominated world grain exports (1920s – early 1970s), and the current period of weaning US influence and high third world food dependence. By reading his piece, today’s reader can get a more holistic perspective of the current global food crisis faced by the war in Ukraine.

Picture by Jonathan Petterson, Unsplash

Figure 1: A history of crises (real global food price index)

Source: Xu (2019), Mitchell (1988), Grilli and Yang (1988), FAO, Bonsai Economics. Note: the different lines refer to different data sets used to derive each global food price index series

1850s-1917: the UK at the centre of the world

The UK was the first country to industrialise, which eventually contributed to rising longevity and higher living standards, all of which led to the rapid increase of its food demand. Domestic food production failed to keep up with this boom, which combined with Britain’s world dominance at the time, led it to become a major food importer. While the UK sourced roughly 10% of its wheat from abroad in the first half of the 19th century, the ratio reached close to 80% by the beginning of WWI. Wheat came primarily from Europe (Russia, Germany) and the Americas (US, Canada, Argentina).

1920s-early 1970s: the US as the world’s food superpower

A key turning point in the world food system occurred after WWI, when the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the subsequent civil war abruptly disrupted Russian grain exports to the UK and Europe. It was at this point, that the US rapidly increased its food production to support its European allies, becoming by far the world’s largest grain exporter. In fact, during WWI, the US supplied the UK with half of its wheat imports and during the reconstruction period from 1919 to 1926 it shipped 6.2 mn tons of food to Europe. This boom in US food production was the root of the later difficulty of US overproduction, as the Great Depression and WW2 created difficulties in finding markets to export. This contributed to the growing US exports to third-world countries, marking the starting point of their growing food dependency.

1980s-today: third-world dependence and a drop in US influence

A food crisis began in the late 1960s, as the USSR started to rapidly improve the living standard of its citizens, turning itself into a major food importer. In fact, in 1990 the calorie intake in the USSR matched the US, while Soviet citizens consumed equal or more meat than their counterparts in the UK (even though the latter were much richer otherwise). The lack of a sufficient supply response to this rising demand led to a period of booming food prices, with the crisis reaching a conclusion with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the subsequent living standards drop.

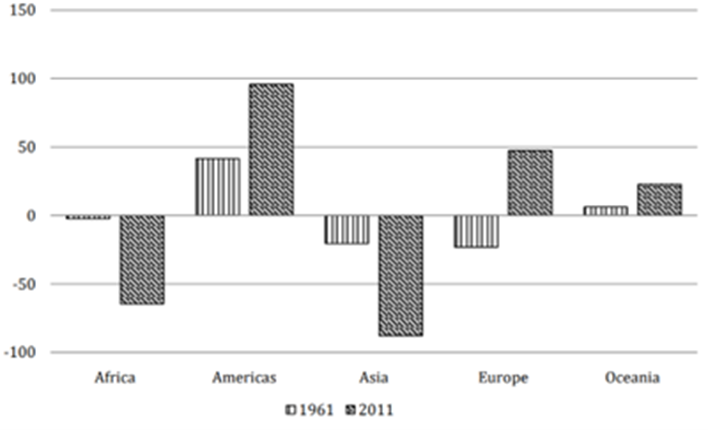

In parallel to the Soviet dynamics, this was also an era when the US and Europe further solidified their food exports to the third world. In fact, as it is shown in Figure 2 below, the second half of the 20th century saw Africa and Asia becoming increasingly reliant on cheaper American and European grains.

Figure 2: Africa and Asia became major net importers of grain (net cereal exports)

Source: Xu (2019), FAO, Bonsai Economics

At the same time, it was also a period of weaker US influence on the grain market, with its share of world exports declining from the 1980s onwards (see Figure 3, below). This partially reflects the rising food production in Europe, with Russia and Ukraine being vital parts of the current food regime.

Figure 3: US cereal export share has been declining (US world cereal export share)

Source: Xu (2019), FAO, Bonsai Economics

Some concluding remarks

In total, the food market seems to have followed a classical commodity pattern of supply and demand misalignments creating market boom and bust cycles. At the same time, its great importance for social welfare implies that a degree of self-sufficiency, particularly in the global South, may be justified. This is especially the case as soil degradation and the growing use of agriculture land for biofuel threaten future supply from the US and elsewhere. And this is without accounting for the current war at ‘Europe’s breadbasket’.

Comments